Welcome! This is a theme study on cultivating trust and relationships in Research-Practice Partnerships on computer science education. This is a living document and will be updated as the RPP projects develop over time. (The current edition was published on September 26, 2018.)

What’s an RPP?

Research-Practice Partnerships (RPPs) were developed as a new approach to facilitating communication and collaboration between education researchers and practitioners who are directly engaged in delivering instruction and building understanding in the K-12 space.

The RPP setting is intended to focus on problems of practice seen as most important and most impactful by K-12 practitioners who are steeped in the daily challenges of rigorous, equitable instruction. These challenges may overlap with those encountered in higher educational classrooms by faculty, but the challenges faced by K-12 practitioners teaching CS and CT are constantly shifting in light of a continuous cycle of policy changes. RPP’s seek to change the focus of research-informed instruction so that it may be adopted broadly and works for a wide range of practitioners in various settings. RPP teams, consisting of researchers and practitioners, do so by creating authentic, long-term, relationships based on mutual trust, communication and shared agency. An effective RPP can both drive actionable, relevant research while also embodying scholarly rigor. (Want to know more about the basics of RPP? Check here and here.)

Why RPPs in Computer Science Education

At this moment, the larger Computer Science Education community has a lot to gain from K-12 practitioners and CS and Education faculty collaborating more closely. Each population has something valuable to gain from the wisdom of the others.

Since computer science education is a new and quickly growing field, pedagogies and interventions are being developed and implemented at a rapid pace. Practitioners can gain insight into the latest research and a highly informed network by collaborating with researchers. CS education researchers stand to gain an up to the minute understanding the facts on the ground in the classroom and the landscape of dynamic CS education implementation in K-12 classrooms through more direct collaboration with practitioners.

Furthermore, the rapid evolution of CS education necessitates that those implementing CS education in schools not only be included in, but help to drive a constant iterative cycle of research and development. As a result, in 2017 The National Science Foundation (NSF) put out a call for participation in the first round of Computer Science for All Research Practitioner Partnership grants (CS for All: RPP). Those interviewed as a part of this study were all members of RPP teams who received that first round of funding. In order to keep current with the rapidly changing landscape of CS education, the NSF has issued a second call for participation in 2018.

Assessing Research-Practice Partnerships: Five Dimensions of Effectiveness

As a resource to support research-practice partnerships working toward greater effectiveness throughout different stages of the growth and development of such a partnership, William T. Grant Foundation published a five dimension framework to provide a snapshot of RPP effectiveness. The five dimensions were developed after a careful review of the RPP literature and a subsequent round of semi-structured interviews with around ten leaders from nationally recognized RPPs. Growth indicators for RPP teams were developed as a result of these interviews. After further refinement, the final revised framework was presented at a Design Based Implementation Research (DBIR) workshop and at the National Network of Education Research-Practice Partnerships (NNERPP) in the summer of 2016.

Highly effective RPPs devote attention and resources toward

1. Building trust and cultivating partnership relationships

2. Conducting rigorous research to inform action

3. Supporting the partner practice organization in achieving its goals

4. Producing knowledge that can inform educational improvement efforts more broadly

5. Building the capacity of participating researchers, practitioners, practice organizations, and research organizations to engage in partnership work

Each of these five dimensions is accompanied by a list of indicators to more specifically identify what success and growth look like in an RPP. Partnerships in early stages of formation can only easily chart growth in some of these dimensions (like building trust and cultivating partnership), while more mature partnerships can show significant achievements toward knowledge production and sustained capacity building within the partnership. The goals represented in the framework were reflective of researchers and practitioners who were actively engaged in partnerships, both in the desires they had for their programming, and in the accountability outcomes they felt funding agencies and other stakeholders should expect.

What does Trust mean in the WT Grant Foundation Framework?

Trust, as experienced in an effective RPP, is a powerful lever for Computer Science education research. The framework’s highlight on trust reveals a valuable but slippery currency for education researchers interested in generalizability and wide adoption of high leverage educational practices. Trust is an essential component to RPP’s in that it helps all parties work toward equal contributions to the various aspects of the project and its outcomes. That said, “trust” as a characteristic can ensure smoother collaborations in other CS education research paradigms as well. Classroom collaborators are often recruited as a requirement of funding, but promoting trust among collaborators can elevate the participation of classroom practitioners to enhance the broad applicability of project outcomes.

Barriers to an equitable partnership include rare opportunities for researchers and practitioners to interact, limited time, perceived or real power imbalances between practitioners and researchers, differing definitions of “evidence”, and gaps in values or priorities. Indicators that effectiveness in this area is growing include demonstrated respect and accommodation of various team members’ day to day work demands and professional roles, a strength-based mindset about the diverse perspectives various team members bring to the work, establishment of collaborative norms and practices across all stages of the project and partnership, a regular schedule of collaboration, and prioritization of joint decision making.

Data

Health Assessments. Prior to the work of this study, four of the six participating teams utilized a preliminary health assessment tool, developed by Sagefox Consulting Group, as an initial snapshot with which to gather information about the state of the team’s process as a working RPP. This tool, based on the framework proposed by Henrick et al., is of potential value not only to RPP teams but also to those from other research communities who seek to reflect on the overall health of their research design process. It is worthwhile to note that the health assessment was completed by each team in February of 2018 at a national computer science education conference and occurred early in the evolution of individual RPP teams. The results of the initial health assessment showed a wide variability how teams saw themselves and their progress as an RPP at that point in time and it further allowed them to document their progress. The health assessment is meant to be a dynamic tool used by teams over time to reflect on their current state and gain insight that may help them to adjust course and strengthen both the way the team works together as well as their approach for addressing problems of practice.

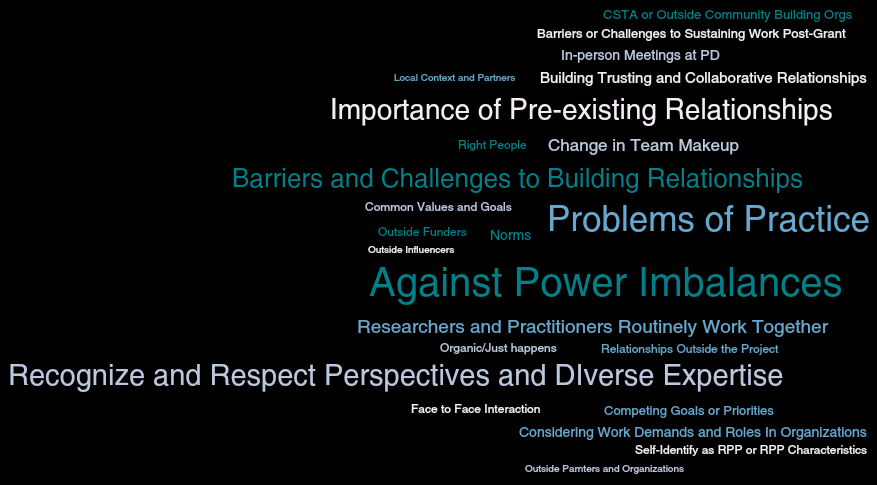

A basic qualitative interpretive analysis was used for this study. [4] This process included the use of a structured coding scheme which was created based on the first domain of the framework created by Henrick, et al., [2]

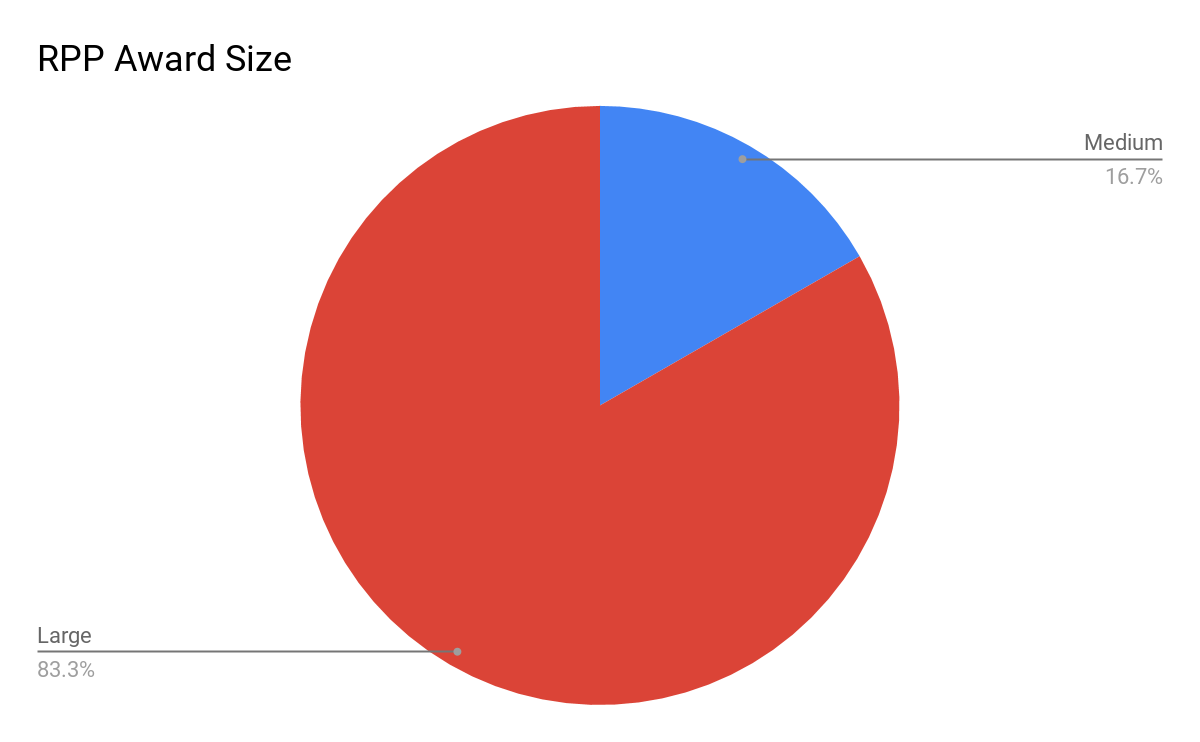

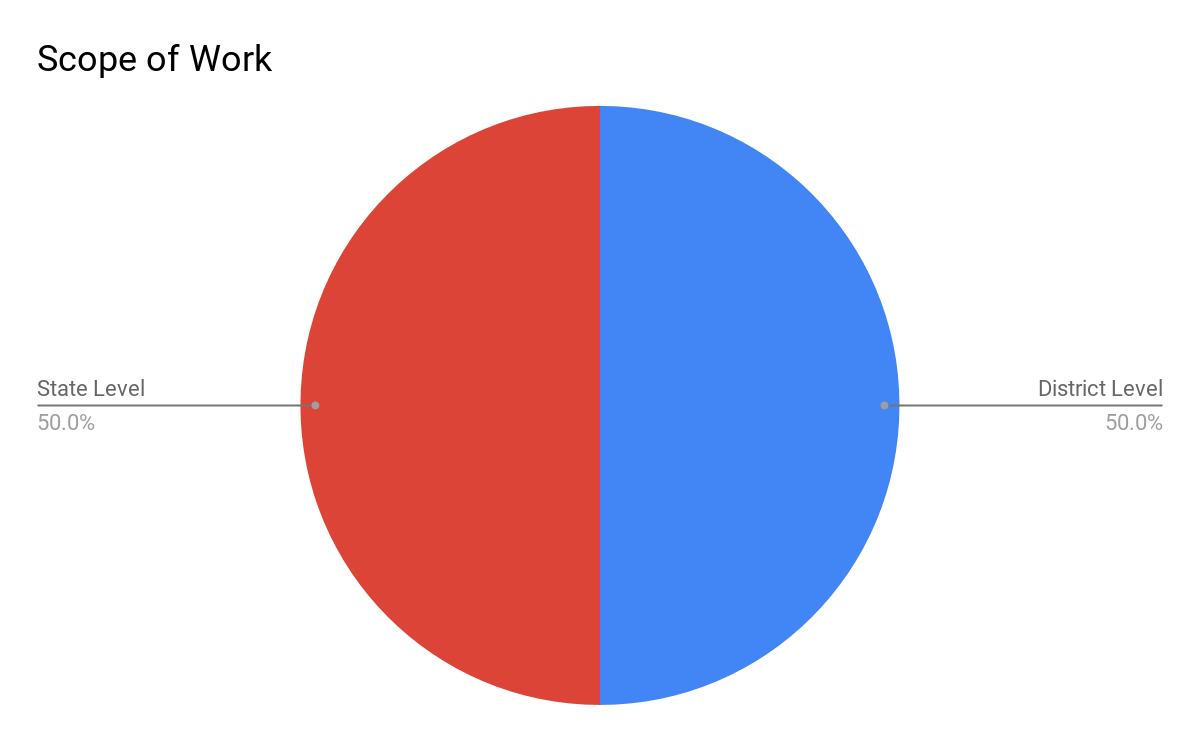

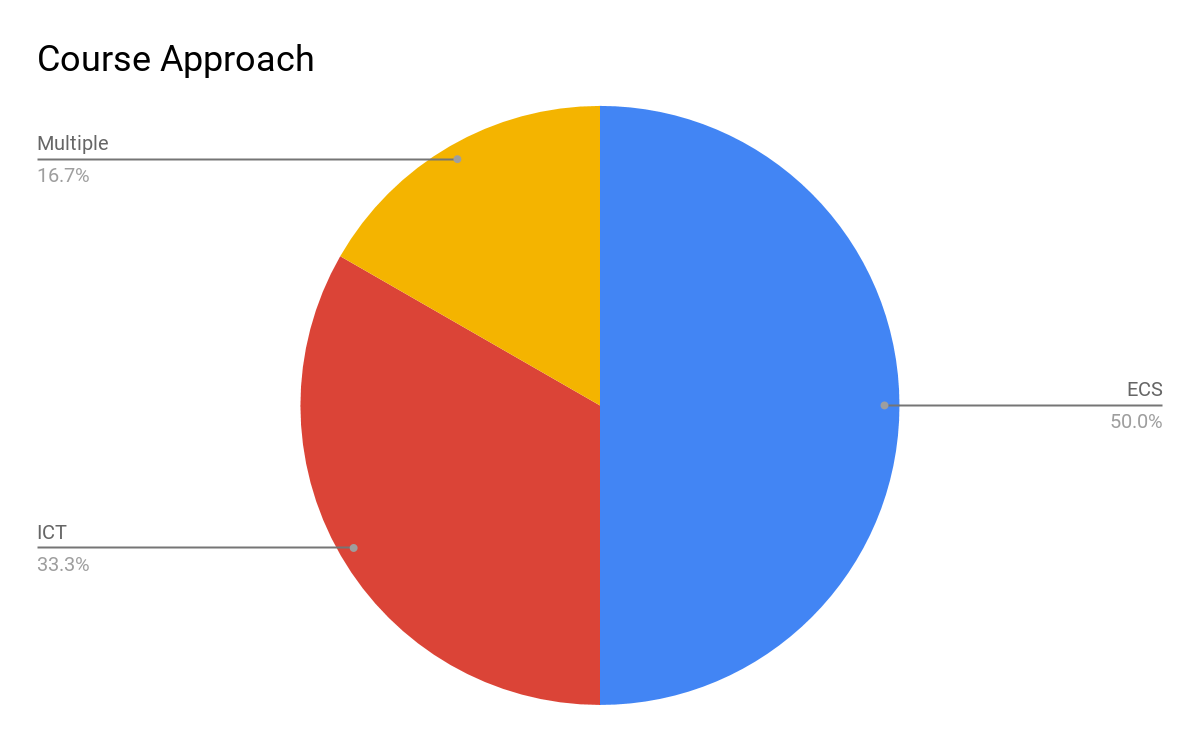

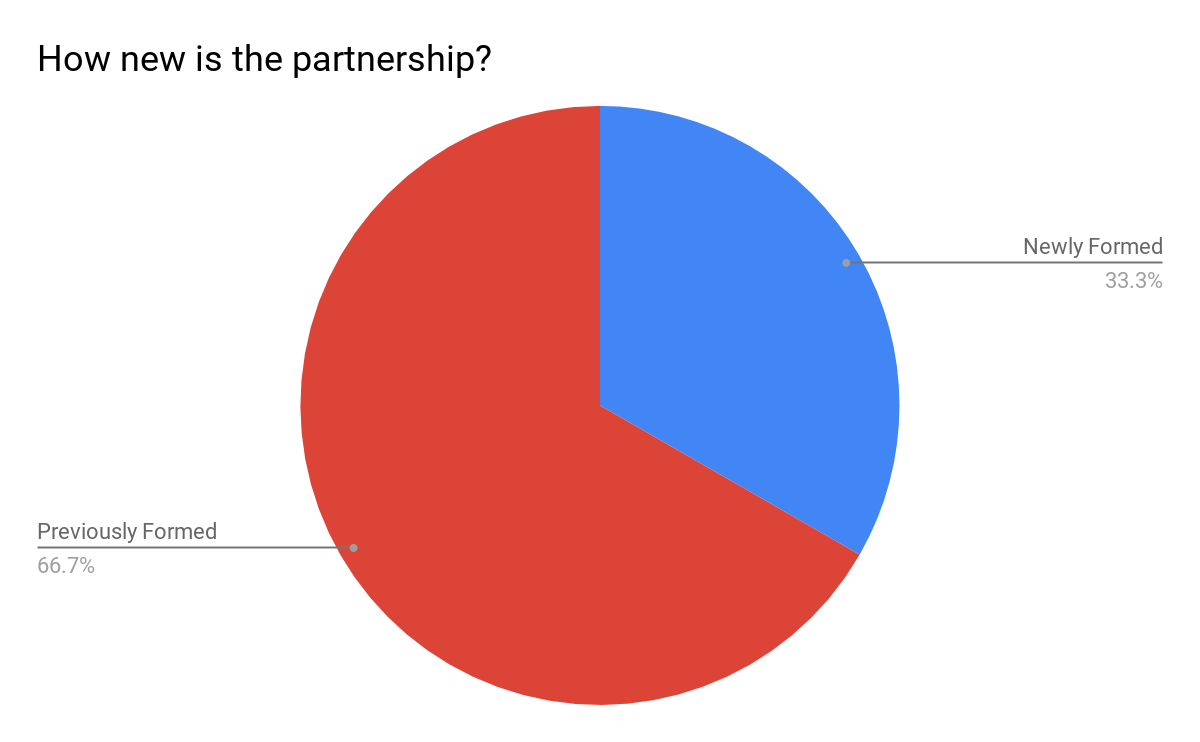

Participants were recruited from six RPP grant awardee (2017)teams from across the United States. The timing of the award, combined with the timing of the interviews means that all teams had been operating for at least 8 months. Participating teams varied in many respects, including the size of the RPP award (16.7 % medium,83.3% large), the scope of their work (50% district level, 50% state-level work), the approach course used (50% Exploring Computer Science, 33.3% integrated computational thinking, 16.7% multiple curricular approaches) and whether the teams were newly formed specifically for the project or were building off of previous work(33.3% newly formed, 66.7% based on existing work).

Due to the nature of RPP work, there was an express effort to include multiple practitioners in the study. In all, eleven participants were interviewed, including two computer science faculty advisers, five researchers, two teacher practitioners and two administrative practitioners.

Interviews for this study were conducted to answer questions about how RPP teams went about building and sustaining trusting and collaborative relationships. The barriers and challenges faced by RPP teams was also a point of interest. Interviews took place in-person and were also conducted through video calls. All interviews were audio recorded and transcribed by a transcription service. They were then checked for accuracy by the first author who also functioned as the sole interviewer.

Each participating RPP team was initially treated as a separate case. After the initial analysis was completed, a cross-case analysis was completed that focused on the similarities and differences in how teams worked to establish collaborative and trusting relationships. For example, teams described how they communicated in ways that were designed to address power imbalances, but that communication varied greatly in the method, the frequency and by whom initiated the communication.

Preliminary Trust Findings related to the Indicators

Researchers and Practitioners Routinely Work Together

Trust is strengthened when researchers and Practitioners routinely work together. Across all the RPP teams in the study, researchers and practitioners made working together towards common goals a priority. The six teams in the study spent varying amounts of time working together and collaborating in many ways, often utilizing multiple means of communication depending upon the needs of the group and their situation. For example, in one rural RPP, meetings were often held through video conferencing as teams members were distributed across the state and face to face meetings were impractical. Other teams focused on the way they structured their meetings to ensure robust communication.

Variations were often the result of the size of the RPP’s focus, the number of team members involved or whether the team was already established when the RPP had begun or was created for the sake of the grant. Some teams described a desire to include additional administrative practitioners but found it challenging due to the competing demands faced by those administrators. For example, one researcher noted, “We do have a plan. We haven’t yet put it in place yet, but we do have a plan as well for a principal group of practice that Aletta would convene, which would be similar. I don’t think that we can get away with having monthly meetings with all these principals.”

Collaborative Decision Making and Guarding Against Power Imbalances

Effective RPP teams established routines that promoted collaborative decision making and guarded against power imbalances. Every team interviewed expressed their desire to ensure that all team members were able to contribute to the collective work in meaningful ways on a regular basis. Multiple RPP teams spoke of purposefully structuring meetings so that there was always a practitioner perspective present. This theme of establishing collaborative routines appeared in the interviews of all six RPP teams who participated in the study. Another obvious priority for the teams was to make sure that all members felt safe in offering ideas and disagreeing with other team members. For example, one researcher focusing on how power dynamics can shift depending upon locale, described being intentional about not having team meetings on the university campus. They focused instead on having all meetings take place on school district grounds so that practitioners might feel more comfortable. Other teams cited the importance of spending time together socially away from work as a major factor in building trusting and sustainable relationships. The creation of routines such as these also served as a mechanism by which the team could weather challenges that may arise as a result of the shared work.

RPP Members Establish Norms of Interaction that Support Collaborative Decision Making and Equitable Participation

Team members in effective RPPs establish norms of interaction that supported collaborative decision making and equitable participation in all phases of the work. In the context of RPP work, it is helpful to see norms as the enactment of belief systems working against the typical constraints imposed in more top-down research cultures[3]. All RPP teams had established norms of interaction that governed their working relationships and these could be as simple as being purposeful about the naming of a project group. Other teams made decisions around norms which dealt with larger, more structural aspects of the RPP grant such as who would lead various teams or have access to funding.

Only three of the six RPP teams interviewed spoke of purpose-fully setting norms and there seemed to be some confusion over how norms of interaction differed from the collaborative structures that supported those norms. Many of the teams reported that norms were not overtly established, but were implicit or simply came about organically, due to the right mix of individuals or adherence to a common vision. Nonetheless, many teams expressed the idea that trust was often a result of teams working together through adverse situations that arose over time. As they saw that they could rely on team members to accomplishing tasks, trust was developed

RPP Members Recognize and Respect One Another’s Perspectives and Diverse forms of Expertise

Team members of effective RPPs recognize and respect one another’s perspectives and diverse forms of expertise. One team expressed their belief that it was essential, despite the vast geography associated with their work, that one of the principal investigators make face to face contact with all school partners so that the partners both felt valued and so that the team had an understanding of its collective strength. Five of the six participating RPP teams spoke about the need to identify and acknowledge individual and group expertise. This often meant that cultural shifts were made that were not normally associated with traditional research projects.

Some teams emphasized shifts that took place such as when teams became too large to hold meetings that allowed all perspectives to be shared and it was logical to break them up amongst expert groups that reported out centrally. Others also discussed the importance of acknowledging diverse perspectives and expertise and concluded that it was an essential move in creating trusting and vibrant collaborative relationships. Sometimes teams utilized either administrative or teacher practitioners as co-PI’s on the grants a way of acknowledging their importance to the project and highlighting their perspective and expertise.

Partnership Goals Take into Account Team Members’ Work Demands and Roles in Their Respective Organizations

Researchers and practitioners (of all types) have widely varying work responsibilities and demands. Purposefully acknowledging and respecting the demands of all team members is essential to the creation of a healthy RPP project and in ensuring its sustainability. Local, collaborative approaches such as RPP’s, will best succeed if issues around competing demands are first sorted out. Conservation of Resources (COR) theory suggests that individuals face challenges related to resources loss. When a resource such as time is limited or diminished by the addition of new tasks or demands, identification with one’s work and the ability to complete that work may falter[1]. This theme emerged in the interviews of four out of six teams who participated in the study. Making sure that team members have responsibilities that are in line with their capacity (as well as interest and expertise) was seen as an important step in making sure the RPP work was both productive and enjoyable, as well as sustainable.

Emerging themes

Several emergent themes surfaced as a result of analysis of the interview data. One prevalent theme was the importance of team members holding common values and vision. This theme was echoed by both researchers and practitioners. They often spoke of the power of a unified vision in building trust and helping team members make decisions, and in overcoming barriers. Most of those interviewed did not speak as to how this unified vision was developed nor could they offer specific ways in which they sought to build consensus in achieving their visions. Often, it was described as occurring organically or due to the team simply having the right mix of people.

More than half of the teams described important relationships with outside partners or organizations. Multiple interviewees spoke of the importance of their local Computer Science Teachers Association (CSTA) chapter in being a middle ground and meeting place where researchers and practitioners interacted and where ideas for research (problems of practice) were explored. Other teams spoke of the advantages of having outside funding partners who allowed them more leeway in how they spent grant funds. Outside influences were cited by two groups as championing the teams research, providing publicity and offering support in various ways.

Outside partnerships were often reported as preceding teams’ RPP work. Pre-existing relationships were themselves noted as highly important to many of the teams interviewed. Sometimes those relationships were the genesis of the RPP team potentially a result of a previous grant or other work partnership. Teams with pre-existing relationships often felt they had a head start in their RPP work. They often spoke of feeling unified in their vision, being able to overcome obstacles and being more in tune with team members strengths and diverse perspectives. Evolved communication structures were also reported by teams that had long standing relationships. The gift of increased time together clearly holds some advantages for RPP teams in many areas.

Resources related to Trust

This preliminary of study six RPP teams working on projects related to computer science education gave a snapshot of the teams work to develop trust and build collaborative partnerships. As teams advance in their work and subsequent new RPP for CS grants are awarded. This dynamic project will be updated with new lessons learned. While there are great many things to be learned from the six RPP teams in this study, the act of creating and sustaining trusting and collaborative relationships built on problems of practice is a nuanced and often difficult process. For further resources aimed at helping RPP teams in this endeavor look here:

- Research Practice Collaboratory: Toolkit for Building Relationships

- National Network of Education Research Practice Partnerships: RPP Partnering Up

- WT Grant Value Mapping Activity

- National Center for Research in Policy and Practice, A Descriptive Study of the IES Researcher–Practitioner Partnerships in Education Research Program: Final Report

References

[1] Jonathon RB Halbesleben, Jean-Pierre Neveu, Samantha C Paustian-Underdahl, and Mina Westman. 2014. Getting to the COR understanding the role of resources in conservation of resources theory. Journal of Management 40, 5 (2014), 1334– 1364.

[2] Erin C Henrick, Paul Cobb, Kara Jackson, William R Penuel, and Tiffany Clark. 2017. Assessing Research-Practice Partnerships: Five Dimensions of Effectiveness. New York, NY: William T. Grant Foundation. Retrieved November 20 (2017), 2017.

[3] Michael Luck, Steve Munroe, Ronald Ashri, and F López y López. 2004. Trust and norms for interaction. In Systems, Man and Cybernetics, 2004 IEEE International Conference on, Vol. 2. IEEE, 1944–1949

[4] Sharan B Merriam. 2002. Qualitative research in practice: Examples for discussion and analysis. Jossey-Bass Inc Pub.